På norsk

På norskSvein Lund:

Finnmark is the largest county in Norway. It is also the county which both absolutely and relatively has most nature which has not been exposed to destructive interventions yet. Or seen from a

different perspective: Finnmark is the county in Norway which has most nature left to destroy. And the nature in Finnmark is currently more endangered than ever before.

The nature is the basis for fishing, reindeer husbandry and harvesting of the outfields, which again in different ways influence the nature. The nature is also the basis for - and exposed to - leisure activities such as hunting, angling, hiking and snow scooter driving. And the nature also provide the basis for profitable activities such as mining, development of water power, etc.

This has drawn the attention of Norwegian and international money to the county. The government has had and has certain plans for the county. In the meeting between all the forces having interests in using the nature in Finnmark in different ways, the nature could end up being squeezed and become the big loser. But also the traditional ways of using the nature can easily end up losing when meeting big money and state power.

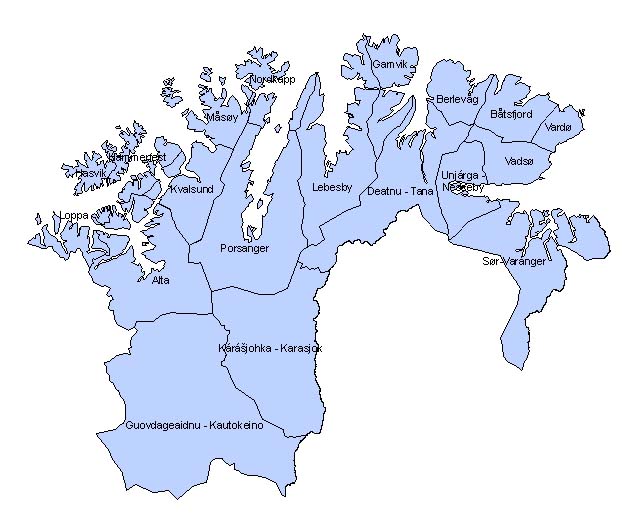

Map of what today is Finnmark county with municipalities |

Map of Sápmi alias Lappland, Laponia or Finnmark |

The Skolt Sami were particularly sorely afflicted by the drawing of the borders, which lead to a permanent tripartition of this ethnic group, with time a great degree of assimilation into the majority populations, and the loss of language and culture. Up to this day the conflicts concerning the use of the nature in this area have still not been solved.

From a historical perspective it's not self-evident that Finnmark is a Norwegian county, that Sør-Varanger is a part of Finnmark and that Ohcejohka/Utsjoki is not. Or for that matter that Kvænangen is not a part of Finnmark. Still I will mainly keep myself to what today is called Finnmark county in the continuation of this text.

The exhaustion of the resources in the fjords, decided and defended by the power in Oslo / Bergen / Sunnmøre, has led to traditional fishing being reduced to a tiny fraction of what it was, and the traditional adaptation to fisherman farmers to scarce remnants. This is both a loss of resources and nature, and as such also an issue for us as a nature conservation movement.

Although, for instance, reindeer husbandry went through great changes as direct and indirect consequences of the introduction of the snow scooter in the 1960's, there is still an unbroken tradition of the knowledge which is needed for the herding within the families, in the siida organization, and in the major part of the knowledge which is needed for the herding.

What can be considered as tradition is a much-debated question. Recently a debater asserted that the spring hunt of ducks in Kautokeino can not be considered a Sami tradition, since the Sami have not produced shotguns themselves. With such exorbitant demands one can define away all traditions, and consequently overrun them.

In older days, when the traditions were formed, there was no clear distinction between livelihood and use. People harvested from the nature, ate what they picked, fished, or caught, and traded or sold what they did not need themselves. To a great extent they lived from a combination of livelihoods, or subsidiary income, as it is called. To the extent they had paid employment, it was often temporary, seasonal, or part time. Now paid employment has become the main livelihood for most people, but simultaneously many have continued to harvest in the traditional manner. In order to speak about traditional use it is therefore not necessary that it is the main income or a registered income, a lot of traditions are connected to what we refer to as "matauk" (increasing the household's food supplies by harvesting from the nature).

In referring to traditional use in Finnmark, I mean the ways in which the local population use the nature for grazing for animals, cultivating and harvesting fodder for those animals, for hunting and catching, fishing in the sea and the lakes, picking berries and other edible plants, woodchopping, and gathering materials for duodji/handicrafts etc.

According to tradition, when one went to the outfields it was because one had something useful to do there, not for sport or recreation. Organized and unorganized hiking just for the sake of hiking, different kinds of sports in the outfield, and hunting and fishing for sport are therefore not part of the tradition.

Ways to use the nature which have been introduced recently also do not belong to the tradition in Finnmark, whether it is fish farming, fishing for king crab or gathering mushrooms and shells for eating.

The traditional use of the nature is practiced by members of a local population, who have felt closely connected to the terrain and landscape they use, and who themselves have been of the opinion that they have the right to such a use, often also the exclusive right or first claim, whether this right has been fixed by law or not.

Traditional use of the nature can roughly be divided into four branches, which traditionally have overlapped: reindeer husbandry, agriculture, saltwater fishing, and use of the outfields (hunting, freshwater fishing, gathering of berries and plants).

The old verdde-system (system of exchange of goods and mutual help) meant that a family or a siida living from reindeer husbandry had special contact with a family living on the coast and often one living in the inland area. These families owned a few reindeers in the herd, and took part in the work with, for instance, dividing, slaughtering and moving the herd to pastures on islands. This arrangement was abolished by law in 1978, something which contributed strongly to destroying the solidarity between the nomadic Sami and the settled population, and led to growing contrasts between these groups. Therefore little is left of the verdde-system today, and to the extent that it still exists it's in more informal forms, as the settled population is not allowed to own reindeers.

Today reindeer husbandry as a subsidiary source of income is mostly a phenomenon within the reindeer herding families, when someone in the family has the reindeer husbandry as the main source of income, while others make a living from other jobs and just take part in the reindeer husbandry in the seasons when they have the possibility to do so.

Ever since reindeer husbandry on a larger scale developed in Finnmark, most likely in the 16th century, it has been organized in siidas. Every reindeer herd was assigned fixed grazing areas for different times of the year and fixed routes of transhumance between these. This system has been continued and is now referred to as reindeer grazing regions, which are regulated from the Reindeer Husbandry Act and the Reindeer Husbandry Administration. But there have often been conflicts between the internal systems the reindeer herding Sami themselves have created and the authorities the government established to regulate the reindeer husbandry. This can be seen in the winter pastures in inner Finnmark, where the siidas traditionally had their respective areas, but these have not been fixed by law. Formally there are large cooperative pastures here, something which has contributed strongly to conflicts among the reindeer herding Sami and to overexertion of the pastures.

Reindeer husbandry is a complex system, and not easy for third parties to understand. It's not possible to measure reindeer pastures in square kilometers and do a calculation of percentage, as mining supporters in Kvalsund do when they assert that the mine will only occupy 3% of the reindeer pastures and it would be sufficient to give compensation for 3% of the reindeers, or as when a politician during the Alta-struggle happily concluded that the entire expansion of the watercourse would only affect the pasture for 21 reindeer.

Different forms of pastures and landscapes need to be available at specific times of the year, and one must also be able to move the reindeer herd between them. If there is only one open passage between two pastures, what happens if this passage is closed? As one reindeer owner put it: If you have a house with two floors and remove the staircase between the floors, you haven't reduced your net living space by 5%, but by 50%.

This way of living was in conflict with the southern-Norwegian farming tradition and the ruling power's ideas about what was modern and future-oriented. That a great part of these fisherman farmers spoke a different language than the official one was seen as just another proof of how old fashioned and outdated they were. Through deliberate colonization strategies great parts of Troms and Nordland were populated by farmers from the south, or often smallholders or redundant farmers' sons who were promised their own land in the north. The regulations of the Land act of 1902 states: "Proprietary rights must only be given to Norwegian citizens and under the particular considerations to promote the population of the district with what to the district, its cultivation and further utilization is a suitable population, which can speak, read and write the Norwegian language and make use of this in the daily life."

The legislation, loan and support systems, and the system of municipal and county agronomists and fishery directors were used to favour those who focused on either agriculture or fishing as the main source of income rather than those who made a living from a combination of the two. What in the end ended most of this old adaptation of livelihoods along the coast was a combination of ideological campaigns and the lengthy influence from harsh juridical and economical realities.

Sami, who in large part fished in the fjords in combination with livestock breeding and livelihoods of the outfield, settled Norwegians, who in large part lived in the outer fishing villages, and season fishermen from Troms and Nordland.

Until the 19th century the right of the local population to fish in their localities was mostly respected. But the fishermen from outside exerted a strong pressure to open fishing everywhere. With time they by a long way succeeded in this, and the result was an endless line of clashes cover the use of these areas and protests from the local population that boats from outside ruined both fish stocks, vegetation of the seabed, and fishing tackle of local fishermen. There have been conflicts between fishermen of the fjords and fishermen of the sea, between fishermen from Finnmark and North-travelers, and also between Norwegian and foreign fishing boats. Russians and Finns have been fishing, in particular in Varanger, from old times, and from the beginning of the 20th century English trawlers have been fishing along the coast of Finnmark, despite the protests of the local population. They have been followed by a number of other countries, and we had a lengthy struggle concerning the border for foreign fishing and fishing with trawls in general.

If one would summarize this history briefly, one could say it has been very difficult for local fishermen to get support from the central authorities for necessary regulation to protect fish stocks, vegetation in the fjords, and the livelihood of the fishermen in the fjords. The capital of the fisheries, with the central point on the west coast, has had a much greater influence than the northern fisheries on the legislation and regulation of fishery by the Ministry of Fisheries and Directorate of Fisheries. And among the fishermen in Finnmark only a few shipowners on the outer coast have had significant political influence, while Sami fjord fishermen and fisherman farmers have had the least influence. The result is that the fishermen in the fjords to a great extent have lost their livelihood. A decisive blow occurred when new quotas also on coastal fishing were introduced by using the excuse of the overfishing of the trawlers, and many small fishermen were denied a quota and thrown on land. When the government in 2006 appointed the Coastal Fishing Committee, many trusted that this injustice would be made up for. The committee did their job, but after pressure from the shipowner-dominated Norwegian Fishing Group the government rejected the entire report. The development has instead gone in the opposite direction, with acts to reduce the fishing fleet and transferable quotas which have excluded a great part of the population of fishermen and prevented the recruiting and continuation of traditions in the fisheries. In their government declaration the new government establishes that this robbery of resources shall be continued and strengthened.

In relation to plans for establishing several protected areas, a few years a go a survey was carried out in Guovdageaidnu on the extent to which people made use of the nature, among other things for picking berries, hunting, fishing and woodcutting. The numbers show that a great part of the population actively uses the nature and that this means a lot to them, both for the well-being and for access to local, good and healthy food. Only a small part of the population sell enough of what they gather from the nature that it produces a registered and taxable income. But many exchange or sell informally and surely many contribute economically to their own households through gathering food, firewood etc. themselves, which they otherwise would have had to pay for. If one asks why people are out in the nature, it is often this aspect of utility which is brought up, but at the same time many emphasise the aspects of health and well-being as well.

Just as the state has wished for solely specialised farmers, fishermen, and reindeer owners who are dedicated to these livelihoods full time, the state has also wished for livelihoods in the outfields to be carried out on a large scale, making a big economic profit. For instance ia rule has been introduced demanding that in order to get dispensation for driving in the outfields for trade purposes, one must have a registered taxable income of at least 50 000 NOK from this specific livelihood in the outfields, for instance fishing or picking berries. Those who do not fulfill this criteria, are then reduced to tourists by the regulations, even though they harvest in areas which have been used by their families for generations.

The traditional livelihoods in the county have to a great extent been protected from foreign acquisition, both because the law sets restrictions and because they have not been very profitable investments. But this does not mean that the areas used for the traditional livelihoods have been left alone from other use of international investment, especially when it comes to mineral industries.

The first mine in Finnmark of considerable size was the copper mine in Kåfjord, opened in 1826 with English capital and leadership. Later Swedish investment replaced the English. Sydvaranger mines were run with German and Swedish capital from 1906 to the Second World War, and after some decades of state management the mine is now owned by an Australian company. The nepheline mine at Stjernøya is now being run by Sibelco, which according to their own information is a "truly multinational business, today operating 228 production sites in 41 countries". The quartzite quarry in eastern Tana was started by a Norwegian company, but has now been bought up by Chinese capital. Of the two mining companies with projects now competing for permission to start, one (Arctic Gold) is a Swedish company with significant elements of German capital, the other (Nussir) is formally Norwegian, but with substantial elements of British, Canadian and Belgian capital. Of the companies which have secured themselves the right to lease in Finnmark, Canadian Dalradian Ressources is by far the biggest, and among the other companies many different countries are represented.

Gradually larger and larger parts of what is now Finnmark became an established part of the (Danish-) Norwegian state, but it's not possible to single out one specific year as the year the county was incorporated. Still the county kept a was unique position, since almost all the land was considered state property. How did the county become state property? The above mentioned letter of 1848 gives this explanation: "The original Finnmark has in fact been considered as belonging to the king or the state since olden times, because it originally was populated only by a nomadic people, the Lapps (Sami) with no permanent dwellings." This quote demonstrates how one thought : Use does not give right to land, if one does not have a permanent dwelling and cultivate the land. This is actually the only known explanation of what later was called Statens umatrikulerte grunn (state owned land not written into cadastre).

When the land was defind as belonging to the state, the state could use the land, and sell the land to whomever it wished to sell to, and that was most often not the ones using the land. The state could also decide who had permission to hunt, fish and pick berries. And since those who used the land locally did not have the documents for it, the state was free to construct roads, power plants, military camps etc. without having to expropriate, the state was the owner of the land after all. While the outfields in southern Norway were in a patchwork of private properties, where only a few chosen people could hunt and fish, Finnmark was open to everyone. As the communication was improved the county became an Eldorado for anglers and grouse hunters from the south. The plain was open to everyone. Who cared that some people without formal legal rights lived here and had been using the resources to subsist and increase the supply of food in the households for generations?

But Finnmark has values under the earth. The Mining Act makes a division between the minerals of the state and the minerals of the landowner. But in Finnmark this division did not make any difference, since the state was the landowner. And the mine manager in Trondheim split and handed out land to whomever wanted it.

The expectations for the act were great, as well as the fear of what the act could lead to of both racial discrimination, privatization, and exclusion of the general public. But after having observed the practices of the Finnmark Estate Agency (FeFo) and the Finnmark Commission until now, we have to say that neither expectations nor fears have been fulfilled. All in all the administration of Finnmark has continued as before but with a different name. And of the changes that have taken place, several have been in the opposite direction than expected. It is claimed that with the Finnmark Act the population in Finnmark finally became the master of its own house. But did it?

While the Sami rights committee proposed that the public administrative agency should be called Finnmark Land Administration, the Storting rejected this and passed the name Finnmark Estate, a name which in itself was a provocation to everyone who doubted that the agency really held the proprietary rights to 95% of Finnmark. But they did get the proprietary rights, although there's the reservation that those who wish to claim proprietary rights to some of Finnmark can report these to the Finnmark Commission. The decisions made by the commission until now do not indicate that this percentage will be particularly reduced.

Several questions remain: what this proprietary right includes, what FeFo has the right to do with its property and what they have the right to deny others to do. These are comprehensive juridical questions. As mentioned before, the property of FeFo finishes at the marbakke (the beginning of the steep underwater slope, which is normally a few metres out in the sea). Therefore FeFo has no authority when it comes to the fishery regulations, threats against life in the sea or oil and gas extraction.

In the Finnmark Act §19 it's stated "Land owned by the Finnmark Estate, can be made into national parks following the rules in The Nature Diversity Act". Resolutions concerning national parks or other protected areas such as nature reserves, landscape protection areas etc. are made by the Storting or the Ministry of the Environment. When a protected area has been established, the centrally-determined rules concerning the use of the area are put into force. In practice this means that when an area is protected, the government takes back the administration of this area from FeFo. The Mining Act establishes that most of the minerals in Finnmark that are now being searched for or asked permission for extraction for, are the minerals of the State, independent of the proprietary owner of the surface land. The proprietary right to these minerals was therefore not included in the proprietary rights passed on to FeFo. Permission for searching for minerals is still being given by the Directorate of Mining in Trondheim, and the ultimate permission for extraction is given by the Ministry of Environment under instructions from the Ministry of Trade and Industry. Development of water power on the land of FeFo can happen upon obtaining a license from NVE (Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate). The proprietary owner can object, but does not possess the rights to anything but financial compensation where economical loss can be proven. The administration of hunting and freshwater fishing is to a great extent executed according to centrally fixed laws, such as the Nature Diversity Act etc. The Finnmark Act also sets strict restrictions on the extent to which FeFo can control this administration.

Several EEA regulations against discrimination of EEA-citizens can put limitations on what FeFo can decide about priorities to or exclusive rights to the natural resources for the local population, the inhabitants in the municipalities, counties or Norway.

Conclusion: When it comes to the important matters which can influence the nature in Finnmark, the population in Finnmark has not become the master of its own house.

Until the Finnmark Act was introduced, there was a law establishing that foreigners could only go fishing in freshwaters up to 5 km from public roads. One of the first things FeFo did was to remove this law, making it possible for foreign anglers to drive on public bare ground trails and snow scooter trails far into the mountains to go fishing. Already there have been complaints that Finnish anglers are emptying the fishing lakes. FeFo claims that the EEA agreement constrained them to change the legislation, but they have still not attempted to insist on their demands and possibly take their case to court.

In a number of cases the FeFo-management decided to give permission for bigger interventions in the nature, such as mining and development of waterpower, and contemporaneously in principle rejected any establishment of new protected areas.

Conclusion: The process of the proposals of the Sami rights committee and the Finnmark Act has made evident and intensified many old conflicts in Finnmark. It has led to many quarrels and caused bad blood, both in the newspapers, within most of the political parties and organisations in the county, and among the common people. Compared to this the practical results of the act thus far have been minimal. One could ask whether it all has been worthwhile.

Most of the changes in the nature in Finnmark are results of the influence of human beings, but we can make a division between direct and indirect influences. I consider indirect the changes that are caused by climate changes. We don't have the complete picture of these changes, and it's difficult to determine to what extent some of these are caused by climate changes or other factors. But at any rate these indirect changes can be mentioned:

– The plain is overgrowing, the tree line is moving higher, and the plain is becoming more grass and less lichen.

– Warmer water in the sea, fish stocks transfer, new fish stocks arriving from the south (mackerel etc.)

– New animal species arriving or spreading (elk, roe deer)).

Among the changes which are more directly connected to human interventions are:

– New roads.

– Much more tracks in the outfields than in the rest of the country – both regulated and unregulated, within and outside trades. Snow scooter wear and tear and disturbance of wildlife.

– Decline of cultivated land. The strong reduction of grazing of sheep in many areas, and the intensification in a few. The goat stock shrinking to nothing. Abandoned fields being used as reindeer grazing land. The remaining agriculture intensifying, and the end of haying in the outfields.

– Increased wear and tear of the vegetation from reindeer husbandry due to a high number of reindeer, fences and use of motor vehicles.

– The strong reduction of fish stocks in many fjords.

– The aquaculture industry has led to a number of effects on the nature: Pollution of the sea and the seafloor, genetic pollution of wild salmon through mixing with escaped farmed salmon.

– Several big fluctuations in the fish stocks due to overfishing affecting herring, capelin, codfish, halibut, redfish and others.

– The disappearance of the sea tangle forest along a great part of the coast and the increase in stocks of sea urchin.

– New stocks of fish and marine animals such as king crab and mackerel.

– Forestry: Some places less, other places more strain.

– Tourism: Cottage areas, grouse hunters, fishing in freshwater and the sea, North Cape.

– Military sites: German from the war and Norwegian later. The destruction and wear and tear on the nature, exclusion of reindeer husbandry / livelihoods in the outfields and pollution from artillery ranges.

– Development of water power: Pasvik, Porsa, Porsanger, Repvåg, Alta. Kvænangen indirectly through the reindeer husbandry.

– Mines and search for minerals: Sydvaranger, Repparfjord, Austertana, Biedjovággi, Stjernøya. Shale in Alta, Loppa and Laksefjorden.

– Actions of preservation have reduced the strain in some areas, natural parks and reserves, but might have led to an increased strain in popular hiking areas.

The nature in the fjords and on the coast outside Finnmark is an important part of the nature in Finnmark. This is threatened by the petroleum and gas activities, from discharges from the mines, and overfishing.

A lot of the nature in the county has already been destroyed, and a lot of the destruction which is taking place on a daily basis is very difficult to put a stop to overnight. Some destructions are irreversible and not all changes should be reversed. We must still have roads in Finnmark, we need bridges and harbors, residential areas and factories. Most of the currently operating power plants should probably be allowed to continue to run, although I have to admit that my big dream is to demolish the dam in Čávčču and start a great project to restore the nature to make the Alta river and valley return as it was, as much as possible. A closer project, which my local group of the Norwegian Society for the Conservation of Nature has introduced, is to restore and revegetate Biedjovággi, to return the mining area to nature and reindeer husbandry.

If we wish to take care of the nature in Finnmark for future generations, both of population in Finnmark and tourists, we should call a "time-out" for further expansion projects now. Furthermore we should return rights to the traditional livelihoods and uses, and ensure that this use will be hindered neither by actions of expansion nor by actions of preservation.

Simultaneously we must not forget that the traditional livelihoods also leave traces. A book about Sami history is called "On soft leather shoes in the history.” But Polaris and Yamaha do not wear soft leather shoes, although the person seated on top of the snow scooter wears a lasso around his neck and chants a joik while driving. We should set an aim of strongly reducing the use of motorised vehicles within the reindeer husbandry and the livelihoods of the outfields, both out of consideration for nature and the people who live by these livelihoods themselves.

There are many ways of using the nature, both traditional and untraditional. Traditions which exist some places are unknown elsewhere. Lastly I will argue for the untraditional uses of the nature, for collaborations between science and the local population to also utilize the nature resources in untraditional ways. We already find a few examples in Finnmark, we have firms producing herbal teas, spices, syrup and pesto from natural products, we have production of cordial and wine from crowberries. This is still on a very small scale, and is only making use of a negligible amount of the resources. If you would like to buy candied Norwegian angelica, cordial of meadowsweet or other delicacies you might be lucky to get hold of it in Sweden.

Finnmark has a long tradition of use of certain medicinal plants, but this has by far disappeared today. Simultaneously our nature is full of other medicinal plants which do not have traditions in the county, but which for instance have been used in Russia, Finnland and other countries. Not to speak of our enormous resources of mushrooms, which rot if not eaten by reindeer or cows. There is a great potential in both the traditional and untraditional uses of nature. A great part of these resources can be harvested for sale and produce income. Just as important is the use of natural products in the households, which makes life and health better in two ways, both by harvest and use. I would also like to argue for the mixing of private and commercial use: the exchange of natural products both with neighbors and acquaintances who live in areas with different natural resources.

But if we are to be able to make use of and further develop both traditional and untraditional ways of using nature, we need to confront the idea that only full-time, year-round work is good enough. The nature in Finnmark provides a foundation for seasonal work and combined livelihoods. I think we need to return to this approach, and back to the mentality where there is no clear division between work and leisure time, between occupation and ways of living.

This will of course mean to face the challenge that this is suitable neither to international economic interests nor to the national power in the south, but the people in the north have struggled against these forces for centuries, so we should be prepared to continue to fight for yet some time to come.

Svein Lund

Leader – Naturvernforbundet i Ávjovárri / Norwegian League for Conservation of Nature – branch in Ávjovárri (Municipalities Kautokeino, Karasjok, Porsanger and Lebesby)